-

Posts

6975 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

66

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Gallery

Blogs

Posts posted by bonanova

-

-

Now, what was it we were talking about? Oh yes ... wherrzzz Beeel? I'll tell you. You know why I tell you? Because Bill would want me to. But this time the old man was not talking to the impossibly gorgeous Beatrix Michelle Kiddo. It was to a guy. A guy who was on a mission to kill Bill. A guy with the name of Al, Jack, Joe or Tom. Which one? Well, it's your job to determine which.

Here's what we know from police interviews that followed the discovery of Bill's cold body on a lonely stretch of country road late last night, along with the fatal gun that belonged to one of them ... the murderer. So read on and see where the evidence leads. But fair warning, exactly half of each of the suspects' four statements are lies.

-

Al:

I didn't do it.

Tom did it.

Sure I own a gun.

Joe and I were playing poker last night when Bill was shot.

-

Jack:

I didn't do it.

Al did it.

Joe and I were at the movies last night when Bill was shot.

Bill was shot with Joe's gun.

-

Joe:

I was asleep when Bill was shot.

Al lied when he said that Tom killed Bill.

Jack is the only one of us who owns a gun.

Tom and Bill were pals.

-

Tom:

I've never fired a gun in my life.

I don't know who did it.

Joe doesn't own a gun.

I never saw Bill until they showed me the body.

Who was the rat who done poor Bill in?

-

Al:

-

Plato: Good morning, class, today's lesson is on probability.

Aristotle: Fantastic.

I'm headed to Vegas this weekend, and I can use some pointers.P: Curb your enthusiasm kid, this is serious stuff.

Here, roll this pair of dice, but don't look at the the result. OK, good.

Now without looking, tell me the probability that you rolled a seven.

If you're going to play craps this is important.

By the way, I can tell you that one of your dice is a four.A: Hmm...

So I could have rolled 41 42 43 44 45 46 14 24 34 54 or 64,

all with equal likelihood, with 34 and 43 making seven.

That's a probability of 2/11.P: You're on a roll kid, now let's do it again. Great.

Again without looking, what's the probability you rolled a seven?

By the way, I can tell you one of your dice is a one.A: So I could have rolled 11 12 13 14 15 16 61 51 41 31 or 21,

with 16 and 61 making seven. Hmm... it's the same as before - 2/11.P: And if I had told you one of your dice was a five?

A: Well ... I guess it really doesn't matter what number you tell me.

It will always come out the same. The probability will be 2/11.P: So what can we deduce from that?

A: That the probability of two dice making seven is ... 2/11.

But wait... Hey, you're not really Professor Plato, are you?P: No. I'm an insurance salesman.

So ... what exactly is the probability of making seven?

-

1 hour ago, bonanova said:

After each man, at random, was given one of the boxes, they were given the following test. Each in turn, and out of sight of the others, was to blindly remove two of the balls from his box, read the label on his box, and then endeavor to tell to the others the color of the third ball, which remained in the box.

Yes. The restriction is only that they can't read each others' labels.

-

Spoiler

Prime factors, FWIW

790 = 79 x 5 x 2

1650 = 7 x 5 x 5 x 5 x 2

464 = 29 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 -

Four identical boxes, each box containing 3 balls, each ball being either black or white, were placed before four men: Al, Bert, Cal and Don. No two boxes contained the same selection of ball colors. Each box bore a label that correctly identified the contents of one and only one of the boxes, but no individual box bore its correct label.

After each man, at random, was given one of the boxes, they were given the following test. Each in turn, and out of sight of the others, was to blindly remove two of the balls from his box, read the label on his box, and then endeavor to tell to the others the color of the third ball, which remained in the box.

It did not seem a difficult task, but the results were a bit surprising:

-

Al:

I've drawn two black balls.

I can tell you the color of the third ball.

-

Bert:

I've drawn one white ball and one black ball.

I can tell you the color of the third ball.

-

Cal:

I've drawn two white balls.

I'm not able to tell you the color of the third ball.

-

Don: (who was blind, and could not read his box's label)

I don't need to draw.

I can tell you the colors of the balls in my box.

I can tell you the color of the third ball in each of the others' boxes.

And then he proceeded to do so. How did he tell?

-

Al:

-

On 6/24/2019 at 1:15 AM, Thalia said:

-

You're right. Nice solve.

SpoilerSpecifying the team of the first player to count would distinguish the teams, if they had been grouped. As it is, it only identified that player's team. I had the grouping in my mind but didn't put the basis into the clues.

-

-

Didn’t all break ... just rules out the case that all broke ... anything else is possible

Between Ed and Jim means beat one and lost to the other.

I have somewhat different answer.

-

Ok what I was looking for is that if no one called their initial then they must have alternated teams when they formed the circle. So that fact didn’t need to be given as a separate condition or assumed. Initials occurring in odd positions of the alphabet must have held even positions in the circle.

-

Sharpen your pencil for this one. Each period is a missing digit.

. . .

X .

=======

X . . Y

. X Y

-------

. Y X YWhat two numbers are being multiplied?

-

When four friends, Bill, Ed, Jim and Tom, began their foursome at Fairview Links last Saturday, they discovered to their dismay that no one had brought a pencil to keep their scores. And well let's just say that in the clubhouse afterward there was some confusion. Here are four "facts" that each player remembered. But fair warning, it turns out only two of each group of statements are true. And, if it helps, they all correctly remembered that no two players had the same final score.

-

Bill:

I beat Jim and Tom.

Ed shot 111.

Jim took 6 on the last hole.

None of us broke 100.

-

Ed:

Bill wasn't last.

I was the winner.

Jim finally broke 100.

I shot 98.

-

Jim:

I beat Bill and Ed.

The last hole was not my best.

We didn't all break 100.

Tom wasn't the winner.

-

Tom:

Ed beat Bill.

I was the winner.

Bill placed between Ed and Jim.

The last hole was Jim's best.

That's it. But surely by now you know what order they actually placed.

-

Bill:

-

In a dream I visited a city named Ten Islands, a charming archipelago connected by a system of bridges, five of which led to the mainland. Four of the islands were serviced by four bridges, three others by three bridges and two others by two bridges. The final island could be reached by only one bridge. The city was well laid out, and the view from each of the bridges provided a new and enchanting visual experience.

I shared the dream later with my son, remarking again and again of the city's beauty.

Even if you hadn't mentioned the fact to me, Dad, I would have told you this was not a real experience, he replied. Ten Islands, as you described it, could not exist in this world, only in a dream.

How could he be certain of that?

-

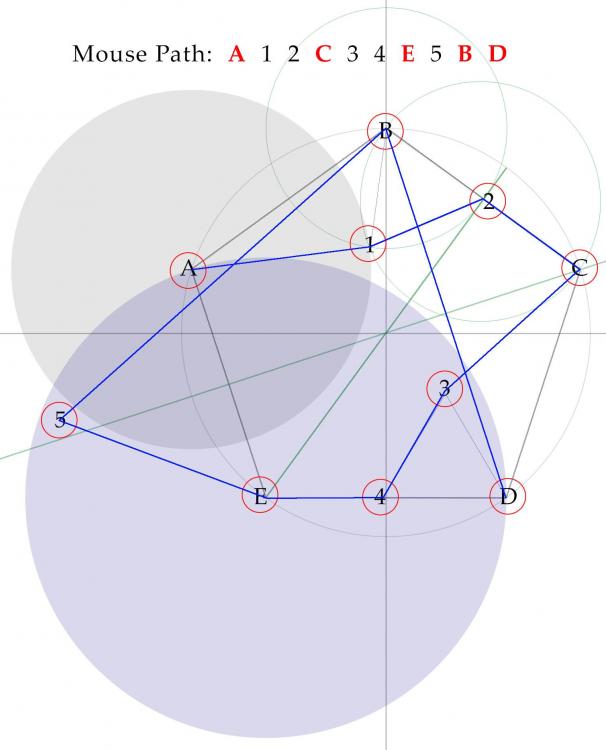

With discussion help from @plasmid, here is a 9-crumb solution. Kudos again for an engaging puzzle.

Spoiler

Each helper is in a circle centered on the previous breadcrumb. The circle excludes subsequent breadcrumbs.

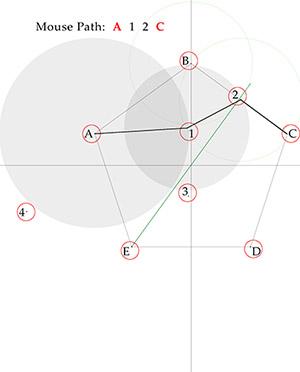

Path A 1 2 C

Spoiler

Circle A includes Crumb 1 and excludes all others.

Circle 1 includes Crumb 2 and excludes all others.

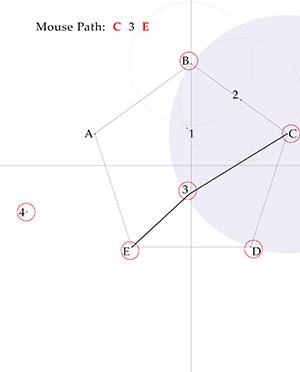

Crumb 2 is to the right of bisector through E and the center, so from 2 mouse goes to C rather than to B.Path C 3 E

Spoiler

Circle C includes Crumb 3 and excludes B and D. (1 and 2 have been eaten.)

Crumb 3 lies to the left of the bisector through B and the center, so crumb E is next, not D.The path from C to E using only one helper is due to @plasmid. I believed it took two helpers.

We can't also shorten the A 1 2 C path, cuz the single helper ends up too close to the center.

The single helpers would end up too close, and mouse would go { A 1 3 E } and spoil things.So there's no 8-crumb solution.

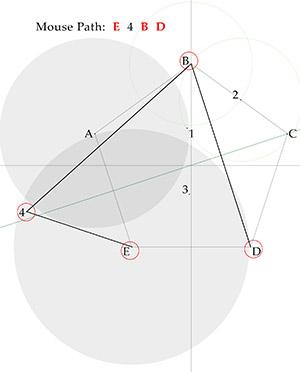

Path E 4 B D

Spoiler

Circle E includes Crumb 4 and excludes D. (Crumbs A 1 and 3 have been eaten.)

Crumb 4 lies above the bisector through C and the center, so mouse will go next to B rather than to D.

At B, only Crumb D remains. -

20 hours ago, Thalia said:

Does the circle alternate between teams? If so...

I asked the players about that last night.

Jenkins, Babcock and Morris recalled they were not standing next to a team mate; then several others said the same.

Smith and Peters agreed, but added that they were quite certain they weren't told to alternate, noting the process was supposed to make home team selection a random process.

They all agreed that it might have happened by chance.

-

What precludes the mouse from going from G(2) to G(5)? (My eyes are getting bleary ...)

-

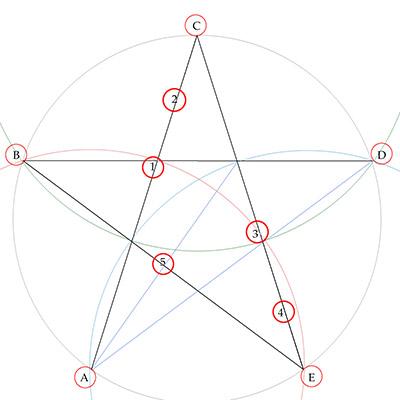

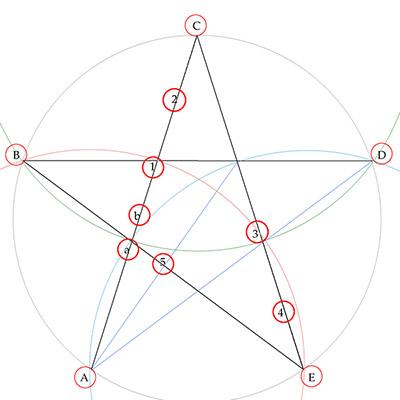

I think there's a proof for the pentagon case.

SpoilerTo answer your spoilered question in your (edited) post.

You need two helper crumbs to get from A to C without encountering B. (1) has to be closer to A than B is, and (2) has to be closer to C than to B. Ditto for getting from C to E without nibbling at D.

And I think it would be provable by drawing appropriate circles, showing there is no way to do either task with a single helper crumb.

Without at least one more helper, the mouse will go from E to D, bypassing the crumb at B. So, 5 helpers, minimum.

-----------

General case ... you can guide the mouse along any desired path, with crumbs placed arbitrarily closely, and possibly finagling things where the path crosses itself. So there exists a minimum (by removing crumbs until at some point things don't work.)

But saying an answer exists and finding it are two different things.

-

This was a fun puzzle.

SpoilerThanks to @plasmid for hinting that OP does not constrain the mouse to travel the diagonals, where the best I can do is 12 crumbs.

A-1-2-3-4-C-5-6-E-7-B-D

If there were to be a 10-crumb, off-diagonal path, it seemed clear that the E-to-B traverse would be the simplest, if one could be found, needing only one helper crumb. The mouse would then eat the crumbs in this order.

A-1-2-C-3-4-E-5-B-D,

Mentally I could get E without difficulty. I anticipated that placing crumb 5 would be the challenge. And making a quick sketch didn't resolve the question. It would be close.

Photoshop to the rescue.

I constructed the partial paths A-1-2-C and C-3-4-E identically. I placed crumb 2 on the BC edge, just lightly closer to C than to B. Then I placed crumb 1 at the vertex of an equilateral triangle B-2-1-B, being careful to nudge crumb 1 lightly toward crumb 2 to insure that distance 12 would be shorter than 1B.

With crumb 1 placed, I drew a circle around A at that radius, to exclude all crumbs other than crumb 1. That was enough to insure the A-1-2-C path would be taken. Constructing path C-3-4-E identically produced no interference, since the previous crumbs had now been eaten, and C was in that sense a fresh start. That gets us to crumb E.

-

I constructed a circle around E at radius equal to the distance ED.

Crumb 5 would have to be inside, to keep the mouse from going to D next (from E.)

-

I bisected the diagram with a line from C through the center.

Crumb 5 would have to be north of that line to make it closer to B than to D.

- Finally crumb 5 would have to be outside the exclusion circle centered on A.

As luck would have it, there was a tiny area that did those three things. I plopped crumb 5 into it, insuring that from E, the mouse would dine next at crumbs 5, B and D, in that order.

The figure is the proof that this placement of crumbs solves the problem. That is, the required inequalities are shown graphically. There is enough wiggle room for each of crumbs 1-5 to make up for any slight Photoshop errors. (i.e. I didn't calculate all the crumb coordinates.)

-

I constructed a circle around E at radius equal to the distance ED.

-

Kudos to the pretty girl in the green dress.

-

@plasmid was discussing finances with his planner the other day.

After they reviewed tax returns and year's worth of receipts, the advice he received was just this:S P E N D

- L E S S

=========

M O N E YYou's think so, he replied, but I've determined that this is quite impossible.

Is he right?

-

1 hour ago, plasmid said:

Edit: To clarify: the mouse doesn't need to travel along straight lines to each of the points. It can go along any curved, jagged, or whatever sort of two-dimensional path you want, which makes the problem more interesting. If that's enough clarification, then don't open the spoiler :3

I understand that the mouse goes to the nearest crumb, and that "nearest" means shortest euclidean (straight line) distance. So (haven't read the spoiler yet) I never conceived the mouse would get advantage by doing otherwise.

I'm assuming the mouse is playing strictly according to his own hunger advantage. Am I right about that?

Oh wait. you're saying that

Spoilerthat the crumbs don't have to be placed on diagonals.

* headslap *

Now I can imagine a solution that adds 2, 2 and 1.

Give me a day or two to work on that?

-

Spoiler

Nice work getting AC to work with only 3 crumbs. It took me four. Nice solve.

SpoilerYour post almost claims a 10-crumb solution!

If you found a 2 on AC, 2 more on CE along with 1 on EB solution, I will be totally in awe. -

@plasmid Interesting puzzle and thanks for the call out.

EDIT: Thought this was optimal, but now have read @CaptainEd's solution.

Tip of the cap, Nice going. FWIW, my best efforts follow ....

Breadcrumbs (red circles) are placed at the five vertices A B C D and E.

Object is for our mouse to take four straight paths: AC, CE, EB, and BD.

Because we have a greedy mouse that goes to the nearest snack, it will move from a vertex to an adjacent vertex whenever it has an uneaten crumb. That must be prevented. So we draw inter-vertex-radius circles -- a red circle centered on A, a green circle centered on C and a blue circle centered on E -- to help define advantageous areas to place our minimum (M) count of additional tasty crumbs to keep our mouse on its intended path.

It is quickly evident that M can't be less than 5. (First-pass solution.)

Spoiler1. Path AC needs an added crumb inside the red circle to keep the mouse from going first to B or E. Similarly Path CE needs one inside the green circle to avoid going next to B or D; and Path EB needs one inside the blue circle to keep the mouse from going next to D. So M is at least 3.

2. But the points on Path AC inside the red circle are closer to B than to C. A second crumb is needed on AC that is outside the red circle. Similarly a second one is needed on CE that is outside the green circle. But Path EB does not need another crumb. So long as the first crumb is placed beyond the bisector of angle CAD. Once we're at crumb 5 the only remaining crumbs are at B (closest) and D. With these additions, M is now at least 5.

3. Once the mouse reaches B he goes unaided to the final breadcrumb at D and we're done. M is still at least 5.

This diagram shows these breadcrumbs, in sequence, as numbers, and we hope for the mouse to visit the points in this order: A 1 2 C 3 4 E 5 B D.But that won't happen. No matter where we put crumb 1 on Path AC, crumb 5 will block either A->1 or 1->2. More crumbs are needed, but how many more? If we can only get to vertex C, crumbs 3-5 can get us home. Path AC is the problem to be solved. We need to insert a minimal number of additional crumbs on AC that will get us past the evil Crumb 5.

Second-pass solution.

SpoilerThis solution provides two additional crumbs, (a) and (b), and thus makes M=7 and total (including vertex crumbs) of twelve.

- Recall that we placed crumb 5 on EB just beyond the bisector of angle CAD. (See 9 below.) This fixes the distance A5.

- Place crumb (a) as far from A as possible, keeping Aa < A5.

- Place crumb (b) as far from (a) as possible, keeping distance ab < a5.

- Place crumb 1 as far from (b) as possible, keeping distance b1 < b5.

-

Place crumb 2 as far from 1 as possible, keeping distance 12 < 15 and distance 2C the least from crumb 2 after that.

That gets us to C, and only crumbs 3, 4 and 5 remain uneaten.

- Place crumb 3 as far from C as possible, keeping it within the green circle. Thus keeping distance C3 < C5.

-

Place crumb 4 as far from 3 as possible, keeping distance 34 < 35 and distance 4E < 45.

That gets us to E, with only crumb 5 uneaten.

- Since crumb 5 is within the blue circle, distance E5 < ED.

- Since crumb 5 is beyond angle CAD's bisector, distance 5B < 5D.

That gets us to B, with a straight shot of BD to the last crumb, at D.

To summarize: Five additional crumbs are needed to navigate the four paths in isolation. (1 2) enable path AC; (3 4) enable Path CE; (5) enables path EB. Two more are needed to prevent complications with crumb 5. (a) prevents A->5 and (b) prevents (a)->5.

Twelve crumbs, in all, will get our mouse from A to C to E to B to D along 4 straight paths.

-

At lunch yesterday four students, Al, Bill, Jack and Tom (last names Conner, Morgan, Smith and Wells, in some order) amused themselves by dealing poker hands to all, with the winner being the holder of the best hand. The winner of the first hand was to collect 10 cents from the other three; the second-game winner would collect 20 cents each; the third winner get 30 cents each; and so on. When the bell rang for afternoon classes to begin, four hands had been dealt, with each student winning once, in this order: Jack, Morgan, Bill and Smith. At the outset Tom had the most money, but at the end Wells had the most.

What are the students' full names?

Lotto Winners

in New Logic/Math Puzzles

Posted

Yes.

I just tried to start with the * operator, seeing that two of the numbers ended in 0,

and looking at prime factors..... seems like a slew of possibilities.

Thought of writing a program.